Unrealized Losses - A BIG Worry

A warning sign before turbulence and despair - a look into unrealized losses in America.

This blog post primarily concentrates on the U.S. market, which is a global leader and the main driver of major financial markets.

What are Unrealized Losses?

An unrealized loss refers to a "paper" loss, which happens when the value of an asset you hold declines, yet you have not sold the asset. The loss is considered "unrealized" since you still possess the asset.

Provide me an example.

If you bought a stock at $50 and its current market value drops to $40, you have an unrealized loss of $10 per share. The loss becomes realized only when you sell the stock at the lower price.

Why bring this up now?

Unrealized losses continue to pose a significant challenge for banks. In Q2 2024, US banks reported unrealized losses on investment securities amounting to $512.9 billion. This figure is sevenfold the peak losses of the 2008 Financial Crisis. Despite a substantial increase in the money supply, the proportion of unrealized losses remains considerably higher. Additionally, Q2 2024 represents the 11th successive quarter of unrealized losses, as persistent interest rate hikes exert ongoing strain on the economy.

Bank of America (BAC), the second-largest lender in the US, has reported $110.8 billion in unrealized losses on held-to-maturity securities, representing 20% of the total. It's no surprise that Warren Buffett is divesting his BAC shares in large quantities.

Banks classify securities as either “held-to-maturity” (HTM) or “available-for-sale” (AFS). HTM securities are not marked to market, so their unrealized losses are not reflected in the bank’s income statement. AFS securities, however, are marked to market, and their unrealized losses are recorded in the bank’s equity.

Meanwhile, in the first quarter of 2024, the FDIC Problem Bank List expanded to include 66 banks, representing 1.5% of the total number of banks. However, this is within the normal range for non-crisis periods of one to two percent of all banks.

Unrealized losses in U.S. banks have been a significant concern, particularly due to their holdings in bonds and commercial real estate loans. These losses are often a reflection of the market value of these assets, which can fluctuate based on a variety of economic factors, including interest rates and the overall health of the economy. When interest rates rise, the market value of bonds typically falls, leading to unrealized losses for banks that hold these bonds. Similarly, changes in the real estate market can affect the value of commercial real estate loans, with declining property values leading to potential losses for banks.

How did we get here?

During the pandemic, banks acquired a significant number of bonds at low interest rates. This period saw a surge in deposits due to stimulus checks and a decrease in consumer spending. With a diminished demand for loans, banks channeled their funds into long-term bonds, like U.S. Treasury bonds, aiming to yield some return on these deposits. This strategy was considered a relatively secure method to gain yield, also driven by regulatory mandates to uphold certain capital ratios, ensuring banks had sufficient capital to withstand potential losses and maintain solvency.

Nevertheless, as the Federal Reserve started to increase interest rates to address inflation, these bonds' values declined. The inverse relationship between bond prices and interest rates means that as interest rates rise, bond prices typically fall.

Cue an example,

Inverse Relationship: When interest rates go up, the market value of existing bonds goes down. Conversely, when interest rates go down, the market value of existing bonds goes up.

Why This Happens: Imagine you have a bond that pays a fixed interest rate. If new bonds are issued with higher interest rates, your bond becomes less attractive because it pays less. To sell your bond, you might have to lower its price to make it appealing to buyers.

Example: Suppose you have a bond that pays 3% interest. If new bonds are now offering 5% interest, people would prefer the new bonds. To sell your 3% bond, you’d need to reduce its price so that its effective yield matches the new 5% bonds.

As a result, banks are now sitting on significant unrealized losses. Note, these unrealized losses grew as the interest rate hikes began.

Does this really matter?

Not necessarily. The losses are considered "unrealized" as long as the banks retain the bonds without selling them at the present reduced prices. Additionally, I believe that capital reserves are significantly more abundant now than they were during the 2008 financial crisis. So as long as there is enough liquidity within these banks, HTM can likely be achieved with the help of the Federal Reserve. Therefore, if they are held-to-maturity who cares, right?

I wouldn't go so far as to say that. Banks may choose not to hold bonds until maturity for various reasons, such as liquidity needs, regulatory requirements, and prevailing market conditions. Do you recall the 2022 event around Silicon Valley Bank (SVB)?

SVB faced a liquidity crisis and had to sell a significant portion of its bond portfolio at a loss. The bank had $1.8 billion in unrealized losses on some bonds at the end of 2022. When it was forced to sell these assets to cover deposit withdrawals, the losses became realized, contributing to the bank’s failure.

Background: SVB was a major lender to the tech sector, with clients including startups and established tech companies. It held a large portfolio of long-term bonds.

Interest Rate Impact: As the Federal Reserve raised interest rates to combat inflation, the market value of SVB’s bond holdings decreased. This created substantial unrealized losses.

Liquidity Crisis: Many of SVB’s clients, needing cash, began withdrawing their deposits. To meet these withdrawals, SVB had to sell some of its bonds at a loss, turning unrealized losses into realized ones.

Panic and Run: News of SVB’s financial troubles spread quickly, leading to a bank run. Clients rushed to withdraw their funds, exacerbating the liquidity crisis.

While the immediate threat has been managed, the possibility of other banks facing difficulties remains. The Federal Reserve's decision to reduce interest rates by 50 basis points suggests this. Remember, there is an inverse relationship: lowering interest rates can diminish unrealized losses as the market value of existing bonds increases.

The REAL Threat

This real threat is essentially two-fold: inflation and commercial real estate (CRE) loans.

As often is the case, a decrease in interest rates typically stimulates economic spending by lowering borrowing costs and increasing cash flow. It is likely that government spending will persist at high levels, especially in an election year. Consequently, there is a risk that inflation may rise again. Such a resurgence of inflation would place the Federal Reserve in a challenging position.

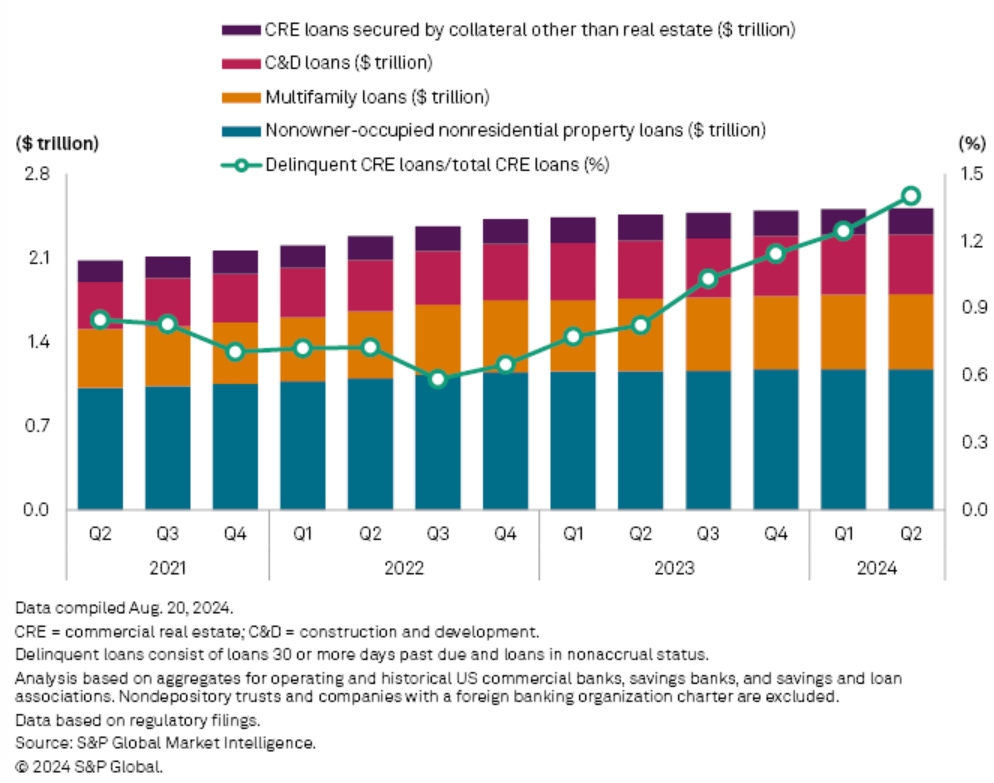

However, CRE loans could present a more significant concern. These loans account for a substantial portion of the total US banking system in 2024. Many were issued at very low rates during the previous decade's low-interest environment, and now, borrowers face the challenge of repaying these loans at today's much higher rates. This situation is exerting tremendous pressure on American lenders who are trying to avoid selling these loans at steep discounts.

Additionally, the situation for CRE lenders is exacerbated by factors such as the slowing economy and the strong post-pandemic shift towards remote and hybrid work arrangements. These have not only increased the distress in the US CRE market but have also had a notably negative impact on US commercial property prices.

Interest rate changes can significantly impact the value of CRE loans held by banks, leading to unrealized losses.

Valuation of Loans: When interest rates rise, the present value of future cash flows from fixed-rate loans decreases. This means the market value of these loans drops, resulting in unrealized losses for the banks holding them.

Borrower Default Risk: Higher interest rates can increase the cost of borrowing for commercial real estate owners, potentially leading to higher default rates. If borrowers struggle to meet their loan obligations, the risk of loan defaults rises, which can further devalue the loans.

Property Values: Rising interest rates often lead to higher capitalization rates, which can reduce property values. Lower property values can affect the collateral backing the loans, increasing the risk of losses if the bank needs to foreclose on the property.

Liquidity and Refinancing: Higher interest rates can make it more difficult for borrowers to refinance existing loans, leading to increased delinquency rates. This can force banks to hold onto underperforming loans longer, exacerbating unrealized losses.

Small banks account for 70% of the outstanding commercial real estate debt. The table below lists the top U.S. banks by the total amount of CRE loans they hold. As many of these loans approach maturity and need refinancing at significantly higher interest rates, the risk of default becomes relevant. Given this context, the question arises again: why would the Federal Reserve initiate the rate-cutting cycle with a big 50 basis point reduction?

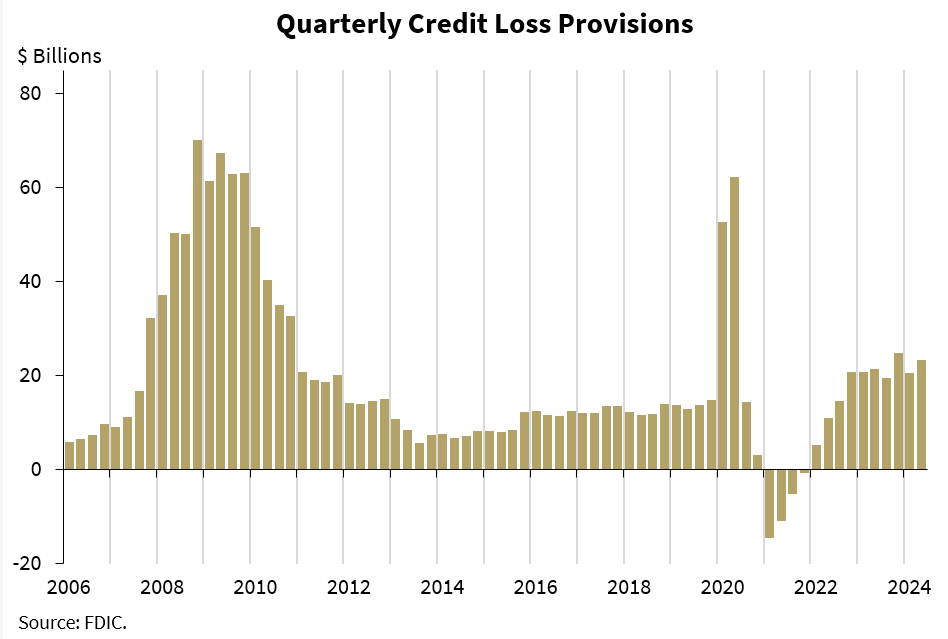

Moreover, credit loss provisions are expected to persist. They currently exceed pre-pandemic figures and are on an upward trend. Whether these provisions will be reduced in the upcoming quarter as the reduction cycle commences is yet to be determined.

The Provision for Credit Losses (PCL) is an accounting measure used by financial institutions to estimate potential losses from loans and other credit-related assets. This provision is set aside to cover expected losses from delinquent and bad debt or other credit that is likely to default or become unrecoverable.

Lastly, I support this concern with the following observation. Guess what is increasing? That’s right, CRE loan delinquencies. Again, I ask, why would the Federal Reserve initiate the rate-cutting cycle with a big 50 basis point reduction? Given the ongoing stress in the office sector that is impacting bank portfolios, it raises the question as to why companies, like Amazon, are mandating their employees' return to the office. Read between the lines. Vacancy rates continue to be high and property values had been plummeting. This situation impacts the loan issuer because the collateral securing the loans diminishes in value. Consequently, this elevates the risk of financial loss for banks in the event of borrower default, since the proceeds from selling the property might not suffice to cover the remaining loan amount. Thus, increasing the provision for credit losses. Full circle.

Sweden is experiencing similar problems.

Connecting the Dots

I often return to the question of why the Federal Reserve initiated a strong start with a 50 basis point cut. Recall the last instances this occurred: during the COVID-19 pandemic response in March 2020 and the financial crisis in October 2008. So, why now again?

It seems there is undisclosed information lurking beneath the surface. Is a soft landing truly expected by anyone? It seems unlikely.

Consider the situation: facing a significant wave of debt maturing in the coming years, the Federal Reserve was compelled to lower interest rates to mitigate the impending pain. Banking institutions likely anticipated this move, as the Federal Reserve collaborates closely with them to ensure the stability of the U.S. financial system. As long as they maintained adequate capitalization, they could endure these unrealized losses, knowing they would diminish with the reduction of interest rates. It appears they have merely postponed the inevitable for a few more years. Moreover, as bond yields decrease, stocks become more attractive, leading to new record highs as we’ve seen recently.

Wrap-up

In addition to the variables mentioned in this blog post, I have not addressed other significant factors such as the substantial credit card debt held by consumers and the impact of the Yen carry trade on financial markets.

As charge-offs, or write-offs, start to increase (which is already happening in the credit card sector), some turmoil is expected. The Federal Reserve is exerting every effort to support the economy, but it faces numerous challenges simultaneously - from inflationary pressures to delinquency rates to unemployment figures. A single decision could inversely impact these factors, so a careful balance is necessary to emerge successfully. With a considerable number of these low-interest loans maturing in 2025 and 2026, caution is advised. While the cycle of interest rate cuts will aid in refinancing, it remains to be seen whether it will prevent the resurgence of inflation and further affect the carry trade.

Indeed, the debt of the United States as a percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP) has escalated to unparalleled heights. This increase in debt could potentially precipitate an unprecedented economic downturn if not managed properly. However, the dynamics involved might be too formidable to prevent such a downturn.

Further to this, comparing the chart of total debt alone to the world's most popular index reveals a clear indication of when the stock market surged to hallucinating levels, which can be easily correlated with the rise in debt levels. It's an interesting observation worth considering.

Piling debt upon debt will not resolve issues. Continuously increasing government spending while incurring deficit after deficit is also not a solution. Continuing to operate the money printing machine could lead to the Federal Reserve's bankruptcy, resulting in hyperinflation, which is a frightening prospect. Look at the interest on debt in America. Wild.

As investors, we’ve had a good run so far, but it cannot continue like this indefinitely. In simplistic terms, with a larger focus on the U.S. government, it needs to go back to creating wealth and generating surpluses to accumulate REAL economic growth. A change is necessary for the betterment of our future.