Quantitative Easing - Simplified

The Mechanics and Implications of Quantitative Easing for Beginners

What is Quantitative Easing?

Quantitative easing (QE) is a way for central banks, like the Federal Reserve in the U.S., to help boost the economy when it's struggling. In simple terms, this is how it works:

Creating Money: The central bank creates new money electronically.

Buying Assets: It uses this new money to buy financial assets, like government bonds, from banks and other financial institutions.

Increasing Money Supply: By buying these assets, the central bank increases the amount of money in the economy.

Lowering Interest Rates: This extra money lowers interest rates, making it cheaper for people and businesses to borrow money.

Encouraging Spending and Investment: With lower borrowing costs, people and businesses are more likely to spend and invest, which helps stimulate economic growth.

Other methods of implementing quantitative easing include offering long-term loans to banks. Central banks may provide these loans to commercial banks at reduced interest rates, with the option to lower the rates further if necessary. This strategy also expands the money supply and stimulates banks to increase lending to businesses and consumers.

In essence, QE is like giving the economy a boost by making it easier and cheaper to get loans, which encourages more spending and investment.

Risks

QE can be a potent tool for economic stimulation; however, it is not without its risks:

Inflation: One of the primary concerns is that QE can lead to higher inflation. By increasing the money supply, there’s a risk that too much money will chase too few goods, driving up prices.

A famous quote by Milton Friedman, “A budget deficit is inflationary if, and only if, it is financed in considerable part by printing money.”

Asset Bubbles: QE can inflate asset prices, such as stocks and real estate, creating bubbles. When these bubbles burst, they can lead to significant economic downturns.

The QE programs following the 2008 financial crisis played a role in inflating the housing market bubble. The heightened liquidity and reduced interest rates resulted in a sharp increase in housing prices, leading to the formation of an asset bubble.

Currency Devaluation: Increasing the money supply can weaken the currency, making imports more expensive and potentially leading to a loss of confidence in the currency.

The QE programs implemented by the Federal Reserve in the aftermath of the 2007-2008 financial crisis resulted in the depreciation of the U.S. dollar. The expansion of the money supply contributed to the weakening of the currency's value on the international market. Just like anything, the greater the supply, the less valuable an asset is.

Income Inequality: QE often benefits those who own assets more than those who do not. This can exacerbate income and wealth inequality.

The QE programs following the 2008 financial crisis resulted in substantial rises in asset prices, including stocks and real estate. Since these assets are predominantly held by the affluent, it intensified the disparities in income and wealth.

Diminishing Returns: Over time, the effectiveness of QE can diminish. If markets come to expect continuous QE, its impact on stimulating the economy can weaken.

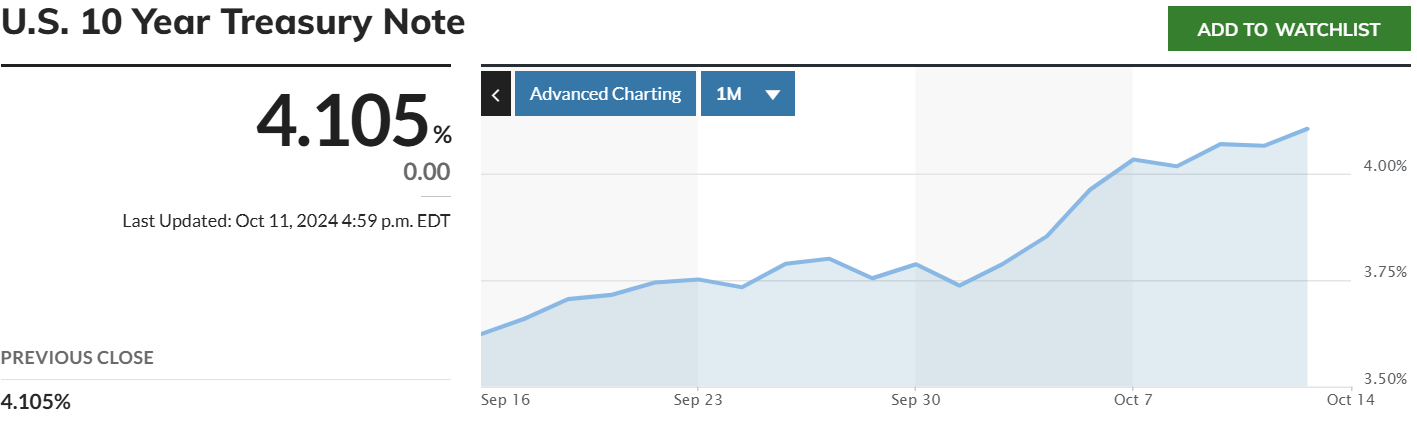

When a central bank purchases more long-term bonds, it typically drives up their prices due to increased demand, which should decrease the yields (or interest rates). However, if the yields rise, it undermines the central bank's actions and can lead to a more difficult economic situation.

Central Bank Balance Sheet Risks: By holding large amounts of government bonds and other securities, central banks expose themselves to potential losses if the value of these assets declines.

Distortion of Financial Markets: QE can distort financial markets by artificially lowering interest rates, which can lead to misallocation of resources and inefficient investment decisions.

When should QE stop?

Central banks halt QE based on a variety of economic indicators and prevailing conditions.

Economic Growth: If the economy shows signs of strong and sustainable growth, the central bank may decide that QE is no longer necessary.

Inflation Rates: Central banks closely monitor inflation. If inflation reaches or exceeds their target (usually around 2% for many central banks), they might start tapering QE to prevent the economy from overheating.

Employment Levels: High employment rates and low unemployment are signs of a healthy economy. If these indicators improve significantly, it may signal that QE can be reduced.

Financial Stability: Central banks also consider the overall stability of the financial system. If markets are stable and functioning well, the need for QE diminishes.

Market Conditions: They look at conditions in financial markets, such as interest rates and asset prices. If these are at desirable levels, it might be time to scale back QE.

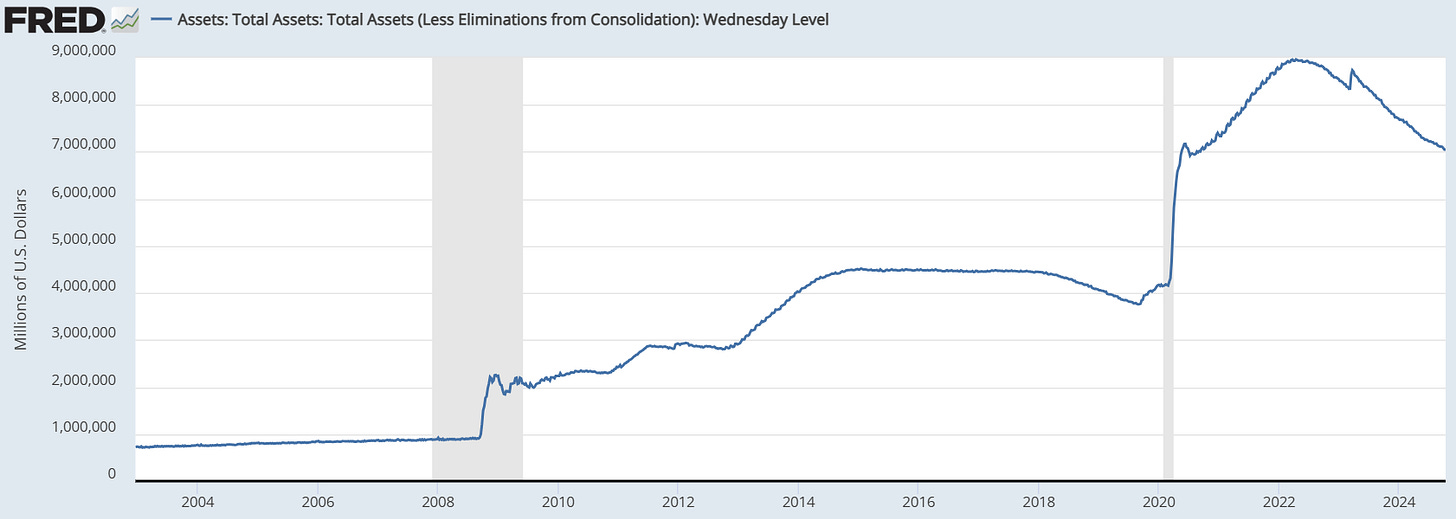

The U.S. Federal Reserve implemented QE in response to the 2008 financial crisis. They conducted several rounds of QE, purchasing large amounts of government bonds and mortgage-backed securities. This increased the Fed’s balance sheet from $882 billion in December 2007 to $4.5 trillion by May 2017. Since COVID-19, it has almost hit a high of $9.0 trillion.

Summation

Quantitative easing (QE) had been utilized before the 2008 financial crisis in Japan and Europe to tackle specific economic challenges. Owing to its apparent effectiveness, the U.S. Federal Reserve embraced and executed QE as a response to the 2008 financial crisis.

QE was first introduced by the Bank of Japan in March 2001 as a response to deflationary pressures and economic stagnation. The European Central Bank (ECB) introduced QE in March 2015 to address low inflation and stimulate economic growth in the euro area.

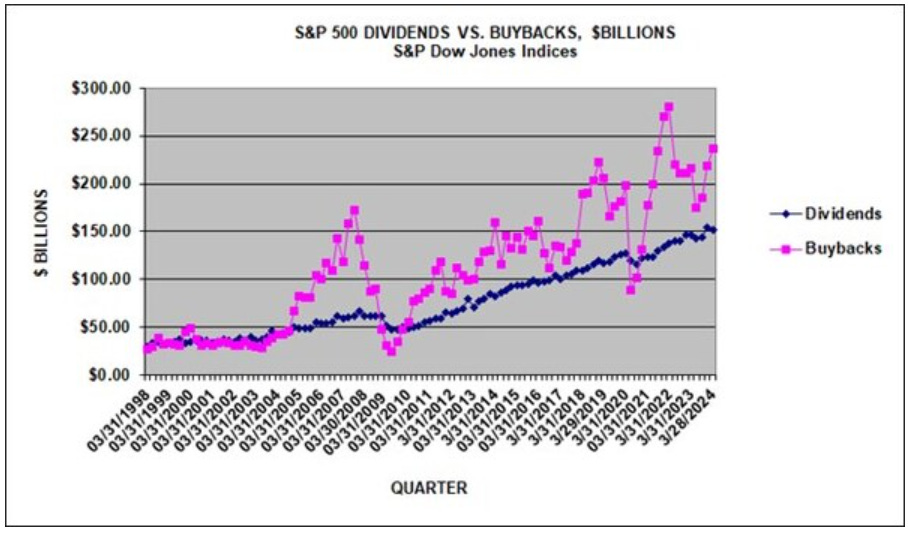

The effectiveness of Quantitative Easing (QE) is a matter of debate. QE aims to stabilize and boost the economy to mitigate severe economic downturns, or revive from them. However, some argue that QE has exacerbated wealth inequality. Rather than supporting wage growth and enhancing economic productivity to reduce prices, it appears to have widened the wealth gap. The influx of new money has disproportionately advantaged financial asset owners, to the detriment of the wider population. Moreover, the consistent increase in buybacks and dividends each year further underscores the point that those holding equities are the primary beneficiaries.

For those that do not understand the magic of buybacks, consider giving this a read.

Final Question

Considering the growing U.S. deficit, the question arises whether Quantitative Easing (QE) will be phased out to curb further public debt accumulation and hold the private sector accountable for poor decisions, or if QE will continue, safeguarding the 'bad actors' at the expense of saddling future generations with more debt.