It’s the Long End That Moves Markets

Understanding the Fed’s Balance Sheet Trap: A Simple Guide for Everyday People and Investors

Ever notice how mortgage rates or car loans sometimes rise even when interest rates are being cut? A recent thread by @_Investinq on X reveals a major shift in how the U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed)—America’s central bank—manages money and bonds. This shift began during the 2008 financial crisis and has left the Fed in a tough spot that affects all of us.

🏦 What Is the Federal Reserve?

The Federal Reserve, or "the Fed," is the central bank of the United States. Its job is to keep the economy stable and healthy by managing:

→ Interest rates (to control inflation and borrowing costs)

→ Money supply (how much money is circulating)

→ Bank stability (making sure banks are safe and sound)

🛠️ How the Fed Does This

→ Raises or lowers interest rates to cool down or boost the economy

→ Buys or sells government bonds (called Quantitative Easing or Tightening)

→ Supervises banks to prevent financial crises

→ Provides emergency support during economic shocks (like in 2008 or COVID)

Let’s break it down step by step, using simple language and everyday examples—whether you’re an average person or an investor, this guide will help you understand what’s happening and what it means for your wallet.

🏦 1. Before 2008: The Fed Was Simple and Flexible

The Fed’s balance sheet was under $1 trillion1.

It mostly held short-term Treasuries—government loans paid back in weeks or months.

These short bonds were low-risk and easy to trade, allowing the Fed to adjust interest rates quickly.

💡 Everyday Example: Think of it like keeping your savings in a checking account—you can pull money out anytime. The Fed was nimble, able to tweak interest rates without affecting long-term loans like 30-year mortgages.

💥 2. The 2008 Crisis: Enter Quantitative Easing (QE)

The financial crisis hit hard—banks collapsed, markets froze, and the economy tanked. The Fed cut short-term rates to zero, but it wasn’t enough. So they launched Quantitative Easing (QE):

What Is QE?

The Fed buys long-term Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS)2.

This pushes up bond prices and lowers interest rates.

Lower rates = cheaper loans for homes, cars, and businesses.

📊 QE Timeline:

2008–2010: $1.3 trillion in MBS to rescue housing3.

2010–2011: $600 billion in medium-term Treasuries.

2011: Sold short bonds, bought long ones.

2012–2014: $85 billion/month, open-ended at first.

💡 Investor Example: QE is like flooding a dry garden with water to help plants (the economy) grow.

🧮 The Shift:

By 2012, the Fed’s bond holdings averaged over 10 years to mature.

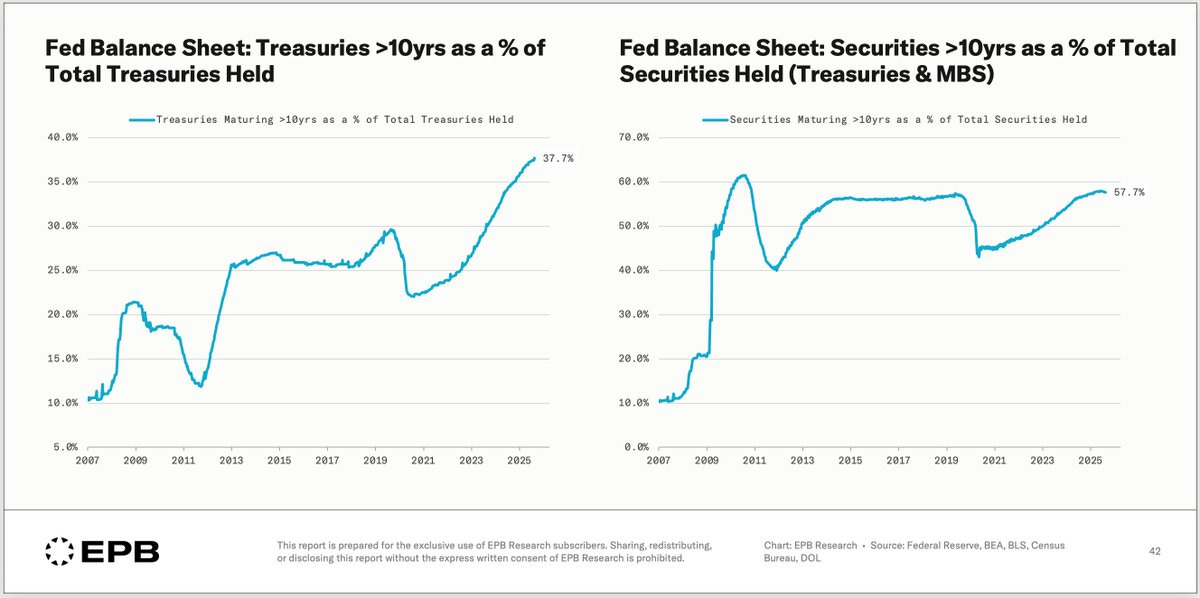

In 2006, <20% of Treasuries were long-term. By 2025, it’s nearly:

38% for Treasuries

58% including MBS

The balance sheet ballooned from <$1 trillion to >$9 trillion by 20224.

⚠️ 3. The Trap: Fed Is Stuck with Long-Term Bonds

Today, the Fed holds:

$4.2 trillion in Treasuries

$2.2 trillion in MBS

Nearly 60% won’t mature for over 10 years5

Why Can’t They Just Sell?

Selling would crash bond prices and spike mortgage rates.

Politically risky and economically damaging.

So they rely on Quantitative Tightening (QT)—letting bonds mature slowly.

💡 Everyday Example: Imagine you have a 30-year mortgage at 3%. If rates jump to 7%, you won’t refinance—you’re locked in. The Fed is like that homeowner, but with trillions in bonds.

⚠️ QT Challenges:

Few bonds mature monthly.

MBS prepayments have dropped—people cling to low-rate mortgages.

QT started in 2017 but hit a snag in 2019 when repo markets spiked.

COVID led to more QE, doubling the problem.

⚠️ 4. QT Hurts More Than QE Helps

Unwinding is messier than building up. Research shows QT tightens the economy twice as hard per dollar as QE loosened it6.

Key Risks:

Rising rates = paper losses on long bonds.

Housing distortion—Fed owns a huge chunk of MBS.

Market volatility—yields jump, affecting everything.

Bank cash shortages freeze lending.

💡 Investor Example: QE is like adding gas to a car. QT is like slamming the brakes—jerky and risky. Your portfolio could drop suddenly, like in 2019’s repo crisis.

The Fed must balance:

Fighting inflation (tightening)

Avoiding market crashes (stability)

📚 5. Historical Lessons & What It Means for You

Historical Parallels:

1940s U.S.: Fed capped bond yields until a Treasury deal7.

Bank of Japan: Owns half its government’s bonds—can’t exit without chaos.

💡 For Everyday People:

Borrowing becomes expensive and unpredictable.

Mortgage rates stay high, car loans cost more, credit cards charge extra.

💡 For Investors:

Watch bond yields—they influence stock prices.

Fed may cut rates early to avoid instability.

Volatility could create opportunities in short-term bonds.

Example: Saving for a house? High rates could delay your plans for years. Investing? It’s like playing chess—predict the Fed’s moves and act early.

🧠 Bottom Line

The Fed has rewired markets by becoming a massive long-term bond holder. Unwinding this will take decades, with losses and drama. It’s not just “printing money”—it’s a structural shift that makes the economy more fragile.

What This Means for You:

Expect higher or more volatile costs for loans and investments—a deleveraging period.

If you’re investing, focus on how rate changes play out—not just headlines.

Deleveraging Period: An Approach to Investing

In my previous Substack, embedded below, there is certainly reason to believe that a deleveraging period is on its way. However, determining when that may happen is quite impossible.

🌍 Broader Economic Effects

Take a look at 30-year yields across major economies—they’re climbing, even after rate cuts. Now imagine what happens to U.S. long-end yields once the Fed begins its own cutting cycle. Don’t be surprised when the long-end keeps surging upward. Understand that printing more money (QE) is not the answer anymore as the risk will be priced elsewhere, likely the long-end.

The Fed holds trillions in long-term Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. Rising rates reduce the market value of these holdings, leading to unrealized losses. Selling long-duration assets becomes politically and economically risky, potentially triggering market volatility.

Connect the dots — Long-end rates directly influence 30-year mortgage rates. A rise makes home loans more expensive, cooling housing demand. Homeowners with low-rate mortgages are less likely to refinance, slowing down MBS turnover and tightening liquidity. Loans for homes, cars, and business investments become more expensive, reducing spending and slowing economic growth. Households renewing mortgages at higher rates face increased monthly payments, cutting into non-housing consumption. Higher rates reduce the present value of future earnings, often leading to equity market corrections. U.S. rate hikes influence global capital flows, impacting emerging markets and foreign exchange rates.

And so, the dominoes fall in line!

Tariffs, Trump, and the Real Estate Cycle

Navigating Tariffs, Trump, and the 18.6-Year Real Estate Cycle: Liquidity, Market Volatility, and Economic Realities.

● Written with the help of GrokConsider joining DiviStock Chronicles’ Referral Program for more neat rewards!Please refer to the details of the referral program.A type of investment that represents claims on the cash flows from a pool of home loans. Essentially, banks or lenders bundle together many individual mortgages and sell them to investors as a single security.